“Money has no motherland; financiers are without patriotism and without decency; their sole object is gain." Ron Paul, End The Fed

And so, the Great Powers stumbled into a conflict that none claimed they wanted. Some of those protestations are more convincing than others. Austro-Hungary had pushed for a localized war, but was prepared to follow through even when it became apparent that the war would metastasise. Russia was largely the reason why it did. Both had territorial ambitions in the Balkans that they were unwilling to sacrifice on the altar of ongoing peace. Serbia also had imperial ambitions, as represented by the Greater Serbia project that was, at that stage, half-complete. France wished to regain Alsace-Lorraine and was instrumental in stiffening the Russian spine.

None of these players could properly lay claim to unsullied motivations. All could have lowered the temperature, but none did. Italy was Italy, fickle, feckless and a Great Power in name only. Britain played little part in the specific crisis which led to the war until too late in the piece, but she had her own motivations, given the fact that British foreign policy of the previous decade had been shaped by the desire to maintain Germany's subordination to Albion. And the Germans themselves? Their need was simple enough:

“German aims before the war began were relatively modest. Basically, Berlin sought an acknowledgment that Germany was Europe's dominant power.”(1)

Which was, of course, the one thing she would not be granted. The political classes of Europe, therefore, chose to sacrifice the citizens whose wellbeing was their primary responsibility to settle matters of 'honour'. The British are as good an example as any. Six million men were sent to France and Belgium to fight a Germany whose Chancellor had explicitly stated – just prior to the commencement of hostilities – that he sought no territorial gains in France.(2) There was, likewise, no intention of fording the Channel and descending upon Dover. So, what the war emphatically wasn't was a defensive war against an enemy attack, the only type of war for which a justification can be given without hesitation.

So, why was Britain at war? To keep promises that were never explicitly made? To preserve an Empire of captured peoples that had never been at risk? Or, perhaps subconsciously, was a wider war that featured Germany an opportunity to administer a whipping that would not be present were the conflict to remain localized? The patricians in SW1 spoke of national honour (as defined by them), yet Grey, the Foreign Minister, maintained that Britain was unburdened by entanglements and that his hands remained free – free to sign up anyway and send over 600,000 to their deaths.

Not that it necessarily seemed that the conflict would be long drawn-out at the time. The most recent wars – the Prusso-Danish War of 1864, the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 and the 1870-71 Franco-Prussian War – had all featured no more than eight weeks of actual fighting.(3) The 'experts', paying no heed to the forty-plus years of weapon enhancement that separated the last of those conflicts from the present clash, confidently predicted that the troops would be 'home by Christmas'.(4) However, by then it was painfully apparent that this was a war unlike any other and that they had failed to take account of the impact of a myriad of new factors. There was no excuse – the American Civil War, the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78 and the 1904-05 Russo-Japanese War had ushered in some modern tactics that resulted in huge casualties:

“Another factor causing military leaders to tragically misjudge the nature and length of a future war was their fundamental misunderstanding of how such technologically enhanced weapons as rifled artillery, magazine-fed rifles, machine guns, aircraft and more powerful explosives had forever altered the nature of combat. These newer, more lethal weapons had industrialized the practice of war, expanding the relatively compact battlefields of earlier ages into vast killing fields, across which massed formations marching in impressive and colorful array were quickly and efficiently reduced to shattered equipment and scattered corpses.”(5)

Whilst there is serious competition from other eras – not least our own – the epic stupidity of the leaders of the warring nations in the Great War takes some beating. I do not propose to give chapter and verse on the Western Front, but I shall probably provide a little more detail on the war in the East, as that arena has been somewhat neglected in my view. We know that trench warfare in France and Belgium dominated the war in the West, punctuated by even greater carnage when one side or the other felt the need for a 'push' that would break the stalemate, because that plan of attack had proven so effective the previous dozen or so times it had failed. The top brass, particularly that of the Allies, seemed intent on disproving Einstein's definition of insanity.

There was a small window of opportunity for Germany in the initial exchanges. Britain declared war on Germany at midnight on 4th August, ostensibly because the Germans were on 'neutral' Belgium's soil – the same Belgium with whom the British had been secretly allied since 1906, at the latest, as documents from the Department of Foreign Affairs in Brussels attest.(6) The approved narrative makes no mention of the true order of events, which gives the lie either to claims of neutrality or to the justification for the British declaration of war:

“France had guns and troops in Belgium by July 30 and the British had landed in Ostend the same day, facts which went unreported in most American papers.”(7)

Britain, France and Prussia (or now, presumably, Germany) had all pledged to guarantee Belgium's neutrality –(8) thus, the initial breach was not by the Germans, but by the Entente. This despite the British cabinet's decision of 29th July that they were not obligated to guarantee Belgium's frontiers with military force.(9) But the cabinet was split right down the middle, half anti-war and the rest in favour of intervention and the latter faction won out. Even mainstream historians have long accepted that the decision had little to do with any concern for Belgium and much to do with a desire to prevent possible German hegemony in Europe.

Almost a million German soldiers marched into Belgium, fully 80% of their Army at that time.10) Initially, the advance was very successful and by the end of August the British Expeditionary Force, on the left flank, was in headlong retreat. A French advance into Alsace-Lorraine proved to be a dismal failure, costing 260,000 casualties – a sign of things to come.(11) However, the German plan called for a 40 day campaign, the conquering of Paris and the destruction of the British and French armies and, at the First Battle of the Marne (5th-12th September), the wheels fell off.

While they had overrun a large area in northern France and Belgium – and gotten within 25 miles of Paris – they were also exhausted and had outrun their logistical support and at Marne their luck ran out. The French commander proved capable and a Franco-British counterattack threatened to encircle the Germans, who were forced to retreat around 40 miles where they dug in on an escarpment and repelled subsequent attacks.(12) Stalemate ensued, trenches were constructed and the new paradigm dawned upon both sides, each trained only in manoeuvre warfare. The Germans adapted best and inflicted heavy losses. Both sides were still there four years later.

Over two million men had thusfar fought in the campaign leading to Marne and it is estimated that – already – around 500,000 had been killed or wounded.(13) Although the Allies had only registered a partial victory, the Germans recognised its significance. The Kaiser's son, Crown Prince Wilhelm, even told an American reporter that “we have lost the war. It will go on for a long time but lost it is already”.(14) Attention turned to The Race to the Sea, a final attempt by both sides to attempt to outflank each other to the north, but neither managed to land a decisive blow. By mid-November, it was apparent that another stalemate had set in and the Germans faced the prospect of a draw-out, two-front war.

The German screening force in the East, consisting of around 200,000 troops, fared equally well to begin with. When the Russians invaded East Prussia on 17th August, they made a complete Horlicks of it. Spread too thin, with many untrained soldiers, sketchy transport and topography against them, the two Russian armies failed to co-ordinate their efforts and were routed at the Battle of Stallupönen (on Day One) and the Battle of Tannenberg in the last week of August.

At Tannenberg, the Russian First Army was almost completely destroyed, with losses of at least 30,000 troops, plus tens of thousands captured. Its commanding general, Samsonov, escaped the encirclement and then shot himself.(15) The Second Army, mauled at Stallupönen, then faced the victors of Tannenberg – the German Eighth Army, able to move rapidly between arenas due to the East Prussian rail network – and was routed at the First Battle of the Masurian Lakes and ejected from German soil.(16)

Meanwhile, their Austro-Hungarian allies were busy demonstrating just how far they had slipped down the pecking order. On 12th August, they launched their first offensive into Serbia. They were back across the border, on home soil again, by the 19th, defeated by the underdog at the Battle of Cer and down 40,000 troops.(17) The Serbians were pressured into conducting a limited offensive into Syrmia (to attempt to delay the deployment of the enemy's Second Army to the Russian Front) and suffered a bloody nose, but were still in reasonable shape.(18)

And they were given the opportunity to strike back almost immediately as the Austro-Hungarians invaded a second time and were pegged back at the Battle of the Drina, both sides incurring huge losses.(19) But this time, they gained a foothold inside Serbia, from which another massive attack was launched on 5th November. The Serbs withdrew in orderly fashion, but were hampered by a lack of materiel, artillery ammunition being in very short supply. They were even forced to abandon Belgrade, which was captured on 2nd December.

But a combination of a gamble by the Austro-Hungarians – an attempt at a flanking manoeuvre that left a single army against all of Serbia's – the final arrival of ammunition from France and Greece and astute generalship from the Serbian Marshal, snatched victory from the jaws of defeat and a full-strength counterattack broke the enemy's nerve; the Austro-Hungarian armies retreated, once again, back across the border. By 15th December, Belgrade had been recaptured and Serbia was again whole. However, the warning signs were there, for both sides. The casualties were enormous; 170,000 for the Serbs, 215,000 for Austro-Hungary.(20) And then, during the winter, a typhus epidemic wiped out hundreds of thousands of Serb civilians, too. The ability to resist another invasion was severely compromised.

The Dual Monarchy wasn't done yet. They were also trounced by the Russians in Galicia, their eastern crownland within Austria's half of the Empire, in a series of battles, after which the Austrian front collapsed and they were forced out of the entire territory. Between 23rd August and 11th September, they incurred losses (dead, wounded and captured) of around 400,000 men, as against 250,000 for the Russians – a third of the combat troops, including many trained officers – which crippled Austro-Hungary.(21) The Russians, therefore, had chalked up a crushing loss alongside a crushing defeat, the Germans were in the black and the Austro-Hungarians were circling the drain. They were never the same force again.

And the Russians, instead of licking their wounds, decided that passive defence was a non-starter, a decision made possible by the knowledge that the Japanese had declared war on Germany and there was, therefore, no need to commit large numbers of troops further east. So, having retreated from Tannenberg, the remains of the First Army was reinforced and faced the German Eighth Army in what is now north-eastern Poland. German attacks were repelled over three days in mid-September and Russian confidence was restored. A counter-attack featuring a flanking manoeuvre caught the Germans out and they retreated after suffering heavy losses. Subsequent fighting, much of it with artillery, decimated the German army.(22)

The battle also facilitated a new offensive into East Prussia and contributed to victory in the Battle of the Vistula River (near Warsaw), which lasted just over a month, until the end of October. The Russians had assembled half a million men, intending to march west into Silesia. The Germans, with only one army in the East – and little helped by the Austro-Hungarians, who were currently failing in Serbia - were forced to raise another, the Ninth, from troops transferred from the West. A Russian offensive across the Vistula was routed and the Germans reached the river on 9th October. Elements marched north towards Warsaw.

Ten kilometres shy of the city, a set of orders were found on the corpse of a Russian officer. For the first time, the Germans learned that they were facing no fewer than four Russian armies and plans were rapidly reformulated. Now, the plan was to hold the line and allow the Austro-Hungarians, further south, to attack weaker forces across another river, the San. Despite outnumbering their Russian opponents, they made no progress. The Russians attacked in the north and, by mid-October, an entire Russian army was across the Vistula and the Germans were forced into a retreat on 19th October, lest they be cut off.

The Russians sensed blood and launched a general offensive the next day. Multiple bridgeheads were established, across both rivers and German attempts to stem the flow were repeatedly undermined by the threat of encirclement. By the 26th, the Central Powers were forced to retreat to a line 60 kilometres to the west.(23) Both the Germans and the Austro-Hungarians blamed each other for the defeat, although they were at pains to present it as a strategic manoeuvre designed to delay the Russian assault on Silesia. Losses were, once again, huge; 100,000 plus for each side, including 75,000 Austro-Hungarians,(24) but the Russians could better withstand them and, in addition, had rediscovered their mojo.

The Germans reckoned they were done for the winter, but the Russians had eight armies in the field and were keen on using them. Two of them kept the pressure on East Prussia and another three were engaged elsewhere on the Front, but that left three spare for an invasion of Silesia – the Second, Fifth and Fourth.(25) Germany's Eighth Army, the original screening force that had been left in the East, was defending East Prussia, which left the newly formed Ninth Army – recently mauled at Warsaw – and parts of the Austro-Hungarian Second Army.

The Germans, keen to even things up by taking the initiative, put together a cunning plan. They shifted the Ninth north towards the Eighth, reinforced it and attacked the Russian right flank, intending to encircle and eliminate as many troops as possible. This was three days before the planned Russian attack on Silesia, due on 14th November. For eight days, the Germans pushed the enemy back. The Russian leadership in the south, opposite Silesia, appear to have been unaware of the disaster unfolding further north and it wasn't until 16th November that reinforcements were sent; another Tannenberg beckoned.

But superior numbers – Russia's 32 divisions as against Germany's 20 – turned the tide and it was the latter's troops who were obliged to fight their way out of a Russian encirclement, which they accomplished on the 24th as they retreated to the north-east. The Russians achieved a tactical victory in the battle itself, turning defence into attack, but the Germans prevented the attack on Silesia. The Russians retreated to more defensible lines near Warsaw, but they lost at least 280,000 men as against around 160,000 for the Central Powers.(26) Unbeknownst to the Russians, it was the closest they were to come to German soil.

By Christmas 1914, losses were already in the millions and both main Fronts were deadlocked, yet I can find no evidence to suggest that the Allies were having second thoughts. Instead, in the West, they launched a three month assault in northern France on December 20th, despite the fact that shortage of ammunition had been a problem since autumn,(27) a defect that wasn't properly addressed until the summer of 1915. To a considerable degree, the British (in particular) had painted themselves into a corner with their incessant propaganda against Germany. Pride of place went to the 'Rape of Belgium', the tale of German atrocities in the 'brave little country'.

Whilst there is little doubt that the Germans were fearful of francs-tireurs and that they probably shot over 6,000 French and Belgian civilians in the first months of the war, respected American journalists - travelling with the German armies – witnessed no massacres, a point they made in a report to the New York Times.(28) But that wasn't the half of it. In September 1914, Lloyd George had set up a War Propaganda Bureau and recruited twenty five of Britain's best writers to staff it – men such as Arthur Conan Doyle, G. K. Chesterton, H. G. Wells and Rudyard Kipling.(29)

They got to work immediately, producing pamphlets and books at breakneck speed. Conan Doyle repurposed some of the accounts he had written of the Belgian atrocities in the Belgium Congo a few years prior.(30) Now it was the Germans cutting the hands off Belgian babies, rather than the Belgians mutilating Congolese children – King Leopold II's rule being distinguished by casual brutality, famine and a dramatic reduction in population. The British public was also regaled with tales of nurses with their breasts cut off, babies bayoneted and Canadian soldiers being crucified on barn doors.(31)

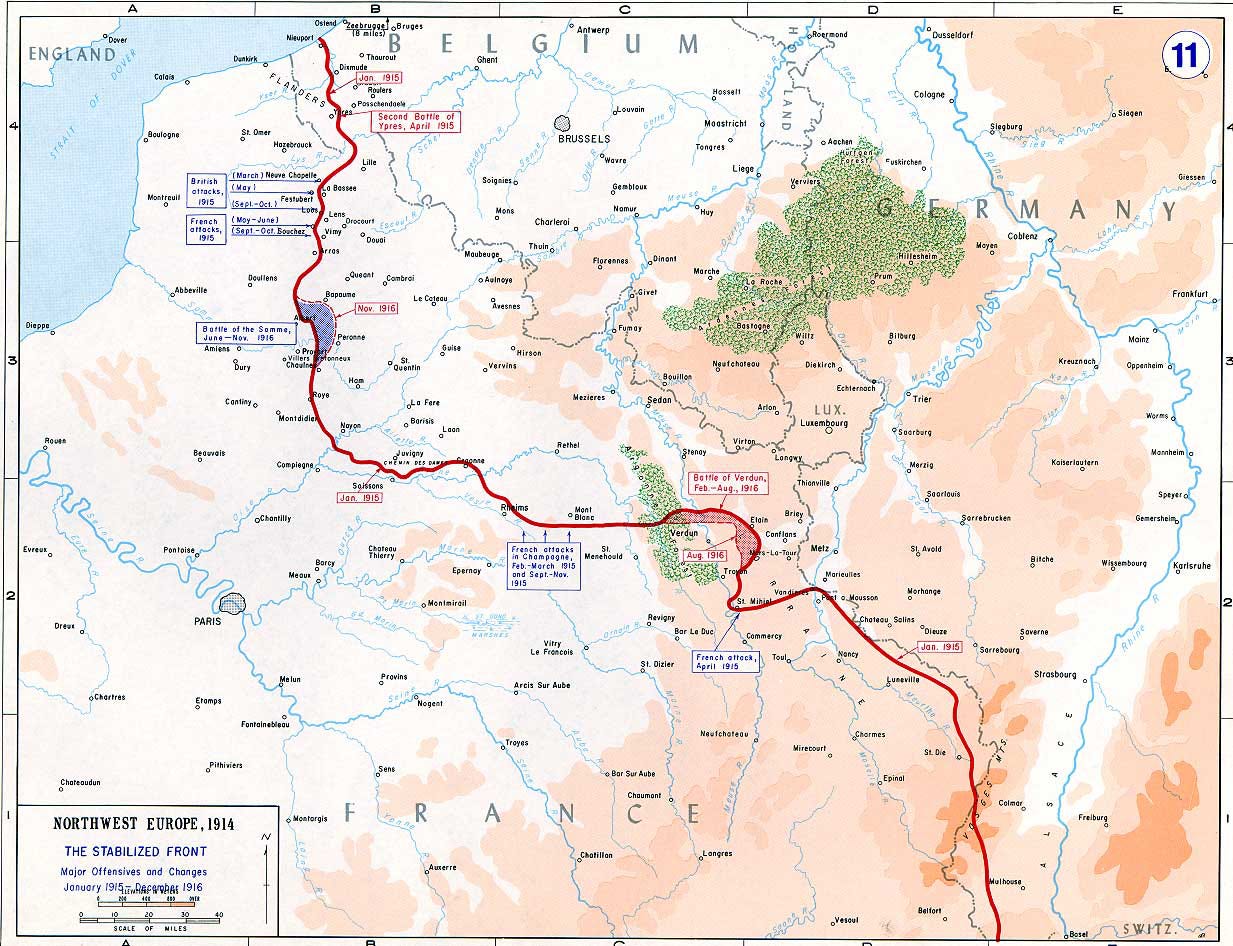

Figure 1

Germanophobia swept Britain and mobs laid waste to German shops, homes and churches. Fifty seven Germans were killed in rioting.(32) “Once a German – Always a German” was the refrain.(33) The Brits spoon-fed information to neutral journalists, particularly those of an American persuasion. They had also cut Germany's transatlantic cable to North America meaning that all telegrams or telephone calls had to travel over British cables.(34) Much of the propaganda was aimed at American public opinion, as much as it was at the British.

The Bryce Report of May 1915 – a work of fiction - went to virtually every newspaper in America and was translated into 27 languages.(35) It contained some of the most lurid falsehoods yet:

“The Bryce Report showed Germans beheading babies and eating their flesh, and contained, among other yarns, stories of how German soldiers sliced off girls’ breasts and executed Boy Scouts. “Eyewitness” accounts told of Germans dragging 20 young women from their homes in a captured Belgian town, stretching them on tables in the town square where each was raped by at least twelve “Huns” while the other soldiers watched and cheered.”(36)

Not unnaturally, a blind hatred of Germany was the result, although – in Britain – it was merely adding to a pre-existing antipathy. However, it's difficult to see how blatant lies that serve to deceive and result in the deaths of millions can be said to be compatible with 'honour'. Instead, “the manipulation of civilian populations for state goals during World War I flew entirely in the face of liberal ideals...” -(37) a classic ruling class ploy that has been rerun numerous times in the intervening years, the 'pandemic' being merely the latest iteration. They do it because it works. It never seems to occur to them that, if they have to lie to do what's 'right', perhaps there's an issue with their legitimacy.

Having accused the Germans of crimes that were too heinous to be go unaddressed, the British state reduced its list of options to one – to fight on, no matter what and defeat Germany. The French characterised the Germans as ogres and, instead of even a hint of introspection, the carnage simply caused the leaders of the Entente to double-down. They further castigated the German Kultur:

“Propaganda made the argument that Germany had relinquished Christian morality for the hard doctrine of Nietzsche and social Darwinism, thus lending even more weight to the moral call to action.”(38)

It was apparent that war aims on either side of the Channel were becoming more defined. Instead of 'honour' as the predominant motivation for continuing the fight, the desire to destroy the Central Powers (read Germany) was now coming to the fore. The battle plan of the French Commander-in-Chief on the Western Front, General Joffre, was a simple one: “We shall kill more of the enemy than he can kill of us”.(39) Thus, when 60,000 British soldiers were either killed or wounded on the first day of the Battle of the Somme in July 1916, the Daily Chronicle felt able to report that “it is, on balance, a good day for the British and the French.”(40) As the French philosopher Henri Bergson had it, it was a “battle of German barbarity versus universal (not just French) civilisation.”(41) It was not enough to defeat Germany – she needed to be permanently put in her place.

But war was expensive – for all – although the Germans were at an inherent disadvantage, exacerbated by the British naval blockade (overseen by Churchill), in place ever since the outbreak of war which, lest we forget, was supposed to be over by Christmas. Hence, by March 1915, a mere nine months into the conflict (and before the carnage of the Second Battle of Ypres and the battles of the Somme, Verdun and Passchendaele), Germany was on the point of surrender.(42) The British blockade was so effective – if that's the correct word – and the Germans were in such desperate need of currency, energy and food that they were prepared to sue for peace.(43)

The British and French, whilst also on their uppers, were sustained by the sham neutrality of the United States and (in the case of Britain) by food and other resources imported from the Empire. By 1915, the Americans had already loaned British and France many millions through US banks.(44) Had Germany won the conflict, the likelihood was that those loans would go unpaid, an unattractive possibility. But a swift end to hostilities was equally disfavoured, as American business was booming. During the period of America's alleged neutrality, GNP went up 20% and manufacturing was up 40%.(45) This trade was almost exclusively with the Allies, as the British blockade precluded trade with Germany.

So the Allies had a problem. If Germany sued for peace now, she would be wounded but substantially intact. And the gravy train would shudder to a halt, whilst Wall Street's opportunity to profit from the blood of others in faraway lands was still viable:

"War is a racket. It always has been. It is possibly the oldest, easily the most profitable, surely the most vicious. It is the only one international in scope. It is the only one in which the profits are reckoned in dollars and the losses in lives”.(46)

But, where there's a will, there's a way, even if the way is wholly perverse and must be a deep, dark secret. The obvious solution was to finance and give succour to the enemy, so that's what was done. The Rothschilds' agent in the United States, the Warburg banking house, was given the all-clear to begin financing the Kaiser. The credit supplied to them by the Warburg and Schroder banking families, who even opened banking institutions in Hamburg after being approved by the Accepting Houses Committee in London, allowed the Germans to fight on.(47)

“The banking and business elites salivating for war included J. Henry Schroder Banking Company, the Rockefellers, the Eugene Meyer family, J.P. Morgan, Alex Brown & Sons, Kuhn Loeb & Co., the Rothschilds, the Warburgs, the Baruch and Guggenheim families and a few others who weaved a tightly connected web of power, money, arms and influence for their own financial gains. Their mutual influence on world affairs often crossed as they financed all sides for a continual, profit rendering conflict.”(48)

Banks quartered in allied countries were, therefore, providing assistance to the enemy. Warburg – and Jacob Schiff of Kuhn, Loeb & Company – were both German-born, naturalized citizens of the United States. His brother was the head of the Kaiser's espionage system and Schiff's two brothers, in Germany during the war, were also active as bankers to the German government.(49) And “the tentacles of the banking families reached deep into the power elites: Dr. von Bethmann Hollweg, was the son of Moritz Bethmann from the Frankfurt banking family of Frankfurt, a cousin of the Rothschilds.”(50)

However, it wasn't just money. Provisions were also required, so the blockade needed to be circumvented, too. The answer was to use an organisation created in late 1914 to feed the Belgians, the Commission for the Relief of Belgium (CRB), spearheaded by none other than future US president, Herbert Hoover.(51)(52) By March 1915, large quantities of food were arriving at Rotterdam (largely from the Americas), given safe passage by the Royal Navy. Some of it went to Belgian civilians and some of it went to the German Army. In addition, home-grown Belgian produce was sent back to Germany to feed the population.(53)(54)(55)

Edith Cavell, a British nurse operating a small hospital in Belgium, “wrote to the Nursing Mirror in London, April 15, 1915, complaining that the "Belgian Relief" supplies were being shipped to Germany to feed the German army”.(56) Shortly thereafter, Cavell was executed (allegedly at British insistence) for aiding prisoners of war to escape, an offence that usually attracts a sentence of three months imprisonment and the show went on.(57) Germany was able to continue to prosecute her war:

“The whole scheme of Belgian Relief was planned for the purpose of securing the enormous food supplies of Belgium for Germany. The Belgian Relief …. was the cause of the prolongation of the dreadful war, with all its horrors and miseries, and the loss of millions of lives...”(58)

But the situation at sea remained delicate. The British blockade, when fully applied in 1914, had caused genuine hardship in Germany and had prompted a submarine campaign, beginning in February 1915, aimed at Allied vessels. The RMS Lusitania, which went down in 18 minutes from a single torpedo strike, was an early victim in April and excellent propaganda. Even today, the official narrative is widely accepted, namely that she was a passenger liner and was sunk contrary to the rules of war. In fact, she was listed in the 1914 edition of Jane's Fighting Ships as an armed merchantman, was skippered by a Royal Navy captain and was carrying weapons and ammunition en-route to Britain, as stated by a US senator and the head man at the Port of New York.(59) In 2006, a dive team discovered thousands of rounds of ammunition in the wreck, although there are an estimated four million rounds still aboard according to the manifest.(60)

A second sinking, that of SS Arabic, in August 1915 added fuel to the fire. As American citizens had been killed when the Lusitania went down, Woodrow Wilson had told Germany that any further sinkings would be regarded as 'deliberately unfriendly'. Three of the crew on the Arabic were Americans.(61) This time, advised by his handler Colonel House, Wilson upped the ante considerably, threatening to sever relations if the attack was found to be deliberate.(62) Chancellor Bethmann and the Kaiser overruled the military and adopted cruiser rules, which provided that “liners will not be sunk by our submarines without warning and without safety of the lives of non-combatants, provided that the liners so not try to escape or offer resistance”.(63) And the United States announced itself on the global stage, in the person of one of the worst presidents in her history.

A detour is in order, by way of explanation. In the first instance, it seems to me that – from here on in – the Allies had the Germans on a short leash. They could control the flow of resources, they controlled the oceans and Wilson was clearly not averse to joining the fray. British and American liners could wend their way through a war zone and German submarines had been at least partially neutered. Hanging around on the surface for several hours while the liner broadcasted their position and disembarked as slowly as possible was likely not an attractive proposition for U-boat skippers.

The odds had shifted markedly in favour of the British and French, yet the Germans fought on, presumably hoping against hope. However, as this scenario is absent from the history books, we are left to speculate as to the German state of mind, but surely the only way to triumph in the West would have been through some grand deception; by somehow stockpiling enough resources for a final offensive which routed the Allies and which could not be forestalled by simply turning off the spigot, a strategy that the Allies were no doubt alive to. Even then, the basic problem would remain – the blockade wasn't going anywhere and, sooner or later, the Germans would be unable to keep an army in the field, nor feed their own people.

In the second instance, the evolution of the United States – or, more particularly, her progressive political class and Wall Street – could do with fleshing out as, despite her potential, foreign entanglements had largely been avoided. This 'isolationism' (the pejorative most favoured by those who sought to meddle in other countries' affairs, when the word 'neutrality' would be more accurate) degraded spectacularly at the end of the nineteenth century, with three separate forays; the Spanish-American War, the seizure of Hawaii and the Philippine-American War, all of which resulted in territorial gains. In addition, the US military had become engaged in a series of interventions in South America, collectively known as the Banana Wars.(64)

With the exception of the encounter with the Philippines - a direct result of the war with Spain over Cuba - all of the conflicts had been confined to America' near-abroad. Clearly, Europe did not fit that category. And the United States was already far-and-away the world's major industrial power, with little to gain by fighting someone else's war thousands of miles away.(65) Additionally, the voting public was firmly of the opinion that Old World grievances were nothing to do with them and, in mid-1915, Wilson was eighteen months away from possible re-election. There was also the small matter of heritage; almost half of America's citizens were of German descent. In fact, German had almost become the national language.(66) The overwhelming sentiment of the American people was anti-British and pro-German.

But Wilson was, in most respects, a front man for other interests, albeit one imbued with extraordinary hubris and a capacity for dishonesty typical of the progressive, for whom the end always justified the means. Until 1910, he had been an academic, latterly as president of Princeton University,(67) but he was manoeuvred into the governorship of New jersey that year by The Money Trust (a cabal of bankers at the heart of the Deep State), most prominently financed by Cleveland Dodge, director of National City Bank.(68) Within a few months, the groundwork was being laid for a run at the presidency. Two thirds of his campaign funds came from just seven Wall Street Bankers.(69)

Come the 1912 election, Wilson was greatly aided by the intransigence of former Republican president Theodore Roosevelt who, when jilted at the Republican National Convention – which nominated William Howard Taft, the incumbent president, no less – ran as a third party (progressive) candidate, splitting the vote and allowing Wilson to romp home with 435 electoral votes.(70) The popular vote went against him 50.6% to 41.8%, but Roosevelt's wilful sabotage proved decisive. In previous campaigns, Roosevelt had been financed by wealthy capitalists, including J. P. Morgan, “the financial potentate of Wall Street”.(71) I would be far from incredulous to discover that the same was true of 1912.

The Deep State now had its man in the White House and, by January 1913, there was no time to waste. The first item on the order of business was to finally institute a central bank, as three prior attempts to make a temporary arrangement permanent had failed, in 1785, 1811 and 1836.(72) The 1907 Panic – a three week crisis during which the stock exchange fell almost 50% - reminded the public that the bankers knew best (when they resolved it), a proposition that they wouldn't have accepted had they known the true story:

“If there was a conspiracy, and the preponderance of evidence [is] that there unquestionably was, it was a joint venture of the Morgan and Rockefeller groups to apportion certain economic domains. The Morgan and Rockefeller groups in this period were intertwined in a number of ventures, and busily traded and bartered positions, one with the other.”(73)

Between them, they eliminated a major competitor – Augustus Heinze, aka the Copper King – and, with the connivance of Roosevelt who handed $25 million of bail-out funds to Morgan rather than the suffering banks, consolidated their control of Wall Street by being selective in who they helped. Morgan even refused to bail out an old friend, who then shot himself, leaving behind a note that said “I do not kill myself because I am a poor man, but because I have lost faith in mankind”.(74) Morgan's propaganda was so potent that he even earned a saintly reputation as the man who 'saved the banks',(75) despite the fact that any funds that he personally handed over were loans at exorbitant interest rates.

“He was touted by many Americans as a true patriot and selfless beacon of financial hope for the country. But, to those who rigidly examined his actions, he was a monster who fed off the demise of economic destruction. . . .”(76)

The case for a 'lender of last resort' now seemed compelling. A commission was empanelled, chaired by the wholly impartial Senator Nelson Aldrich, whose daughter married John D. Rockefeller Jr. and whose son became president of Rockefeller's Chase National Bank.(77) The Aldrich Plan, the fruit of a nine-day secret conference on Jekyll Island (an exclusive enclave off the coast of Georgia) in 1910, attended by agents of the three most dominant banking houses in the world – Morgan, Rockefeller and the Rothschilds – called for the establishment of a National Reserve Association (a banking cartel, misleadingly termed a 'trust'), which would have been unconstitutional.(78) That plan proved stillborn, when control of Congress changed, but the bankers were not to be denied. They knew that

“... central banking along European lines offered vast secure profits for any financial group that could persuade Congress to enact central bank legislation. An elastic fiat and credit system offered power not possible with gold and silver as rigid disciplines on the financial system.”(79)

The full story of the Federal Reserve will be covered in another piece in due course, but a great deal of deception was required. No Wall Street name was associated with the Federal Reserve Act, as it would have been the kiss of death – the public was not enamoured of Morgan et al. Similarly, had they been aware of what the Act truly enacted, it would also have been dead in the water. The same would have been the case with Congress; hence, the secrecy. The only persons with any interest in replacing gold and silver with a paper factory were those who would control the factory – the bankers.

The Act passed the House easily and slipped through the Senate on December 15th, 1913, in four-and-a-half hours, with some Senators stating that they had no knowledge of the contents of the bill.(80) Wilson signed it into law the day it was passed. The second act, a system to pay the private bankers for their future largesse, had already been established with the alleged ratification of the Sixteenth Amendment, which levied an income tax. The bankers obviously favoured secured debt over unsecured, or a tax on the people that guaranteed them a return.

I say 'alleged' because a constitutional amendment requires ratification by three quarters of the states if it is to be adopted. At that time, that meant thirty six in favour. The Secretary of State, Philander Knox, claimed that thirty-eight states had approved, a position that is impossible to justify when his own departmental solicitor devoted sixteen pages to all the ratification errors that he had found. Further, the thirty-eight included California, whose legislature didn't even hold a vote; Kentucky, which rejected the amendment 22-9; Minnesota, which sent no reply to Washington; and Oklahoma, which altered the language of the amendment to have a precisely opposite meaning.(81) In fact, of all the states;

“... not a single one had actually and legally ratified the proposal to amend the U.S. Constitution. Thirty-three states engaged in the unauthorized activity of altering the language of an amendment proposed by Congress, a power that the states do not possess.”(82)

None of which made a blind bit of difference. The federal government's revenue base had been changed from tariffs – largely self-limiting – to an income tax which could be ramped up at will, depending on what the politicians of the day wanted to get America involved in. It vastly increased the power of the federal government and made possible excesses that had previously been kept in check. Which was exactly how the bankers wanted it. There is some evidence to suggest that Wilson himself was duped – according to his private secretary, he believed that he was removing power from Wall Street and he had this to say later:

“Yes. The Federal Reserve Act, which I signed, allowed our system of credit to become too concentrated. The growth of the nation and all our activities are in the hands of a few men who, even if their action be honest and intended for the public interest, are necessarily concentrated upon the great undertakings in which their own money is involved.”(83)

But Wilson is a man who cannot be relied upon. In 1916, his campaign was constructed around the slogan 'He kept us out of the war' when, ten months prior to the election, his envoy Colonel House had negotiated a secret agreement with England and France that pledged America's involvement in the war.(84) Shortly after the war had started, he said that it “may have been a godsend” as “it seemed to open possibilities for his own mission to bring God's order to the world. He was called by God”.(85) That doesn't sound much like a man wallowing in isolationism.

As previously noted, his idea of 'neutrality' involved favouring the Allies at every opportunity, becoming their “supply depot for weapons of war”.(86) Whilst private bankers loaned vast sums, so did the Fed from 1914 onwards,(87) over the repeated protests of Wilson's Secretary of State. The existence of the central bank changed the entire dynamic, as “the US was no longer dependant on British or European money markets [and] there was no danger of drawing down gold deposits”.(88)

It is apparent, however, that without the Federal Reserve, whatever war that may have broken out could not have been sustained for long. The European Powers were slowly bankrupting themselves by maintaining large standing armies and purchasing modern weapons but, by 1900, they couldn't afford a major war.(89) No doubt this fact contributed to the 'home by Christmas' sentiment. Certainly, as noted, Germany was feeling the pinch within nine months.

What couldn't have been anticipated was the extraordinary cynicism of Wilson and others and their decision to allow both sides to be financed. But perhaps the Germans should have known better, had they paid more attention to Wilson himself. He did, after all, leave a conspicuous trail of breadcrumbs. Apologists have attempted to paint him as a reluctant warrior, who came around to the idea of involvement due to German aggression, but Wilson's belief that America was “exceptional” and “indispensable” and his own Messianic convictions do not suggest passivity. If America was a person, she would be fundamentally imperialist:

“What if someone with a documented history of violence against others thought of himself as exceptional, chosen by destiny or God? People would rightfully reject this self-proclaimed greatness and justice toward others, and reasonably conclude that the person making such claims was dangerous or unstable.”(90)

Wilson appears to be the the prototypical poster-boy for 'American exceptionalism' and, when combined with his conviction that his expansionist impulses were, in fact, God's will, it seems reasonably certain that he was always going to seize the opportunity to proselytize at the point of a gun. And so it proved immediately after his re-election (by the skin of his teeth) in 1916. He was untroubled by the prospect of a volte face which shouldn't have been much of a surprise, given his opinion of the masses:

“We want one class of persons to have a liberal education, and we want another class of persons, a very much larger class, of necessity, in every society, to forgo the privileges of a liberal education and fit themselves to perform specific difficult manual tasks.”(91)

But in spring 1915, America was still pursuing 'active neutrality' (whilst allowing the public to be gaslighted by British propaganda) and the blood to be spilled was mostly European. The Germans had decided to make their main effort in the East – it was either that or allow the Austro-Hungarians to sue for a separate peace, due to casualties of around 50% -(92) and transferred considerable forces, creating the Eleventh Army from the troops of both Empires. The Gorlice–Tarnów offensive was intended as a minor German offensive to relieve Russian pressure on the Austro-Hungarians, but turned into a series of actions that lasted the majority of the year's campaigning season – from May to October – and resulted in the Russians' Great Retreat of 1915.(93)

At this point in proceedings, the Russians were being undermined by a number of factors. The war had come two years too soon and there were systemic failures in the structure and function of the armed forces, as well as a bureaucratic morass in the War Ministry. Everything took too long, the command structure was inefficient and disjointed, military production lagged behind and the top brass lacked the skills to wage war successfully.(94)(95) These shortcomings were ruthlessly exposed in 1915 and the Russians lost vast territories, pushed back to a front line that stabilised hundreds of kilometres from the borders of the Central Powers. This line remained almost completely intact until 1917.

The Russians weren't faring much better in Churchill's Folly, the Gallipoli campaign, intended to quench their perennial obsession, control of the Straits. At least they knew where they were – Lloyd George was found “searching for Gallipoli on a map of Spain.”(96) The Entente fleet – comprised of ships from the British, French, Imperial Russian and Australian navies – attempted to force a passage through the Dardanelles into the Sea of Marmara in February and March 1915, culminating in a debacle on March 18th, when several ships were sunk by mines and artillery fire. The plan therefore changed – now there would be a need for boots on the ground, so that the enemy's mobile artillery might be destroyed. The Ottomans, who had failed to distinguish themselves in the Balkan Wars, were not expected to provide much in the way of resistance.

However, many of the officers in the Ottoman Fifth Army were German and their troops were to fight on home soil, an altogether different undertaking. Plus, the British took their time and the four weeks granted the defenders were well spent, with priority given to holding the high ground that overlooked the likely landing beaches. The Allied plan was to get ashore on the southern tip of the peninsula and also to land to the north (which became known as ANZAC Cove) and cut off the Ottomans from the rear. In the south, the Entente landed successfully – incurring appalling casualties – but couldn't secure the high ground, an outcome replicated in the north. Denied a swift victory, the fighting in both sectors developed into another war of attrition, with extensive entrenchment.(97)

Figure 2

An August Entente offensive failed, other theatres demanded resources – the final Serbian defeat in the autumn prompted the transfer of troops from Gallipoli to the new Macedonian Front, the French planned an autumn offensive in the West – and, when Bulgaria declared for Germany in October, a land route from Germany to Turkey was established, permitting an unrestricted flow of weapons to the Ottomans. The Allied decision to withdraw was taken and, by 9th January 2016, the last troops had evacuated.(98) Just about everything that could have gone wrong, did and to what end?

“The Entente campaign was plagued by ill-defined goals, poor planning, insufficient artillery, inexperienced troops, inaccurate maps, poor intelligence, overconfidence, inadequate equipment, supply and tactical deficiencies.”(99)

In the West, trenches were ubiquitous, as we are probably all well aware. The Germans intended to maintain the stalemate in 1915, while they did their thing in the East, but still conducted an active defence, resulting in the Second Battle of Ypres, a month-long attempt to seize the high ground around the Flemish city in western Belgium, infamous for being the first occasion when the Germans used poison gas at scale.(100) They pushed the British back around three miles and demolished the city. And then both sides dug in, once more.

Figure 3

The French and the British launched an offensive at Artois on 9th May, an element of which succeeded initially – to the Allies surprise – but was not sufficiently reinforced. By the time the battle fizzled out, six weeks later, the French had traded 102,500 casualties for the capture of 6.2 square miles.(101) All parties took a breather until the Entente's autumn offensive, again in the Artois region, which fared no better than previously, not helped by the fact that the Germans had been able to observe their preparations from the high ground.(102)

The Allies had outnumbered the Westheer (German army in the west) by 600 infantry battalions but had been unable to achieve a breakthrough.(103) Casualties were, once again, prohibitive, with the French suffering 145,000 in just six weeks. It was apparent that defences in depth were now a thing and that quantity alone was not enough. The Germans concluded that;

“... the lessons to be deduced from the failure of our enemies' mass attacks are decisive against any imitation of their battle methods. Attempts at a mass breakthrough, even with the extreme accumulation of men and material, cannot be regarded as holding out the prospects of success.”(104)

Figure 4

The Chief of Germany's General Staff, General Falkenhayn, concluded that a breakthrough might not be possible and that the only way to win in the West was to “bleed France white” by inflicting massive casualties.(105) To that end, he wanted to pursue a twin strategy; to cut off Entente supplies from overseas and to trap the French in a monumental battle from which they would be unable to retreat and obliterate her armies. But unrestricted submarine warfare was currently politically unacceptable – and, as we have learned, likely to be self-defeating on the resources front – so, initially, he had to settle for the mother-of-all-battles.

On 21st February, 1916, the German 5th Army attacked at Verdun, an important stronghold in northern France, ringed by forts and on the direct route to Paris. Falkenhayn had chosen well. He calculated that he could persuade the French to commit all their reserves, which would then be forced to “attack secure German defensive positions supported by a powerful artillery reserve”.(106) Creating a favourable position without a costly mass attack was the order of the day. He anticipated that the British would mount a relief attack elsewhere and hoped to attrit their reserves, too.

General Pétain, the French commander, gave orders that there would be no general retreat, but counterattacks instead.(107) The Germans made progress initially, French reinforcements were brought into the line and the weather conspired against the attackers, forcing them to pause on the 27th. Another attack, launched on 6th March, achieved further progress, at considerable cost. By 30th March, they still hadn't reached their objectives. The French – and their artillery, in particular – were proving to be worthy adversaries and had, by this time, inflicted 81,607 casualties. It was now clear that;

“...capturing a vital point was not sufficient, because it would be found to be overlooked by another terrain feature, which had to be captured to ensure the defence of the original point, which made it impossible for the Germans to terminate their attacks, unless they were willing to retire to the original front line of February 1916.”(108)

The sensible option would have been to terminate the attack, as the French were doing to them what they had intended to do to the French, yet they ploughed on and, by 21st April, most of their own reserves had been committed to the battle.(109) The Germans had persuaded themselves that the French were losing five men for every two of theirs, but conditions were appalling. Nonetheless, by late June the Germans had advanced to within three miles of Verdun itself and the French had thrown four more divisions into the fray. Then, on 24th June, the preliminary Allied bombardment began on the Somme and, the next day, the Germans suspended their attack. They had suffered 200,000 casualties, as against 185,000 for the French.(110) Six months later the Germans had been driven back and the battle was over.

“Falkenhayn had underestimated the French, for whom victory at all costs was the only way to justify the sacrifices already made; the French army never came close to collapsing and causing a premature British relief offensive.”(111)

The Allies had their own two-pronged strategy to deploy, featuring attacks on both Fronts to ease the pressure on the French at Verdun. In the West, the Battle of the Somme and in the East, the Brusilov offensive, which also commenced in June and which was one of the most lethal offensives in world history. Both caught the Germans off-guard and the 'relief offensives', instead of being sideshows, became the main events.

The Russian attack was launched on 4th June, in eastern Galicia (present-day north-western Ukraine) and represented their obligation under the Chantilly Agreement of December 1915, concluded shortly after the Italians finally made up their minds and joined the Allies. They were scheduled to keep the Austro-Hungarians occupied on a north-eastern Italian Front, whilst the re-equipped Serbians and the Franco-British Armée d'Orient kept the pressure on the Bulgarians in Macedonia.(112) The Central Powers, perhaps a little complacent after their triumphs of 1915, had cycled out many experienced divisions in Galicia and replaced them with raw recruits.(113)

Brusilov's fifty five divisions were opposed by forty nine Austro-Hungarian divisions and fought skilfully. By the 7th, the enemy was in full retreat and the Fourth Army's strength dropped from 117,800 men to just 35,000.(114) Brusilov pressed along his entire front, which “forced the defenders to commit their reserves and left no sectors that could release troops to aid others”.(115) By the 12th, the Dual Monarchy's losses were 205,000, of which 150,000 were prisoners.(116) The Germans had been compelled to send five divisions as reinforcements, but Brusilov wasn't stopped until 8th August. Other Russian commanders, using conventional tactics, were less successful.

The casualty numbers were staggering; half a million for the Russians, at least 150,000 for the Germans and between a million and a million-and-a-half for the Austro-Hungarians.(117) The overall objective was achieved, inasmuch as the Germans were obliged to transfer considerable forces to the East and were, therefore, hindered at Verdun. Russian successes also convinced Romania to enter the war on the side of the Allies (on 27th August), whose armies invaded Transylvania in an attempt to knock Austria-Hungary out of the war.(118) This unwelcome development also demanded German resources as the Romanians steadily advanced, resources which the Allies had incorrectly assumed that the Germans no longer possessed.

The British, as previously noted, had commenced operations on the Somme on 24th June, and the ground offensive was launched a week later. The left wing of the British Fourth Army was decimated on the first day, with over 57,000 casualties – the Daily Chronicle's 'good day'.(119) The French had some success and the Allies had gained a local advantage, which gradually dissipated over the next twelve days as German reinforcements arrived, relieving more pressure on the French at Verdun:

“The battles at Verdun and the Somme had reciprocal effects and for the rest of 1916, both sides tried to keep their opponent pinned down at Verdun to obstruct their efforts on the Somme.”(120)

The British continued to attack through a series of battles, all the way through to 18th November, when the weather forced a temporary lull in proceedings. By then, of the three million men who had fought at the Somme, more than a million had become casualties, with the Allies in the majority.(121) They had advanced about six miles on a front of sixteen miles. Over the winter, the Germans constructed the Hindenburg Line, behind the new Front Line, and made the galling decision to retreat behind it in March 1917, shortening the line by about 25 miles and also voluntarily surrendering the same distance to the enemy (leaving a supply desert of scorched earth behind it)(122) and going over to a strategic defence in the West.

The Romanians didn't have it their own way for long, as “the Central Powers succeeded in taking the strategic initiative in Transylvania by concentrating significant military forces rapidly brought in from the other theatres of operations in Europe.”(123) By December, they had lost Bucharest and the front did not stabilise until mid-January. Importantly, although the Romanian Army had suffered a 30% casualty rate – and been forced to abandon much materiel – it was still a force to be reckoned with, together with Russian assistance. The Central Powers, whilst enjoying a series of successes during the campaign, had failed to achieve their objective of knocking Romania out of the war.(124) Instead, with Allied assistance, the Army regrouped, retrained and recruited and by June 1917, was around 700,000 strong. This was to be a problem for the Central Powers.

An Allied strategy had become embedded, one which their opponents replicated, but with less success. They launched simultaneous offensives either on the same front or on multiple fronts. The two Central Powers – reduced to perhaps one-and-a-half by this stage, with the Austro-Hungarians much diminished – were obliged to fight on both major fronts, plus in Italy, Romania and Macedonia. A coordinated Allied strategy forced them to shuttle divisions up and down the lines and from front to front, reducing their effectiveness due to both transit time and an unfamiliarity with new demands.

Nonetheless, throughout the war the Allies consistently suffered more casualties than the Central Powers, both in terms of dead and wounded – perhaps 50% higher, in fact.(125) By the end of 1916, after the battles at Verdun and the Somme, one might have expected both sides to want to bring an end to the slaughter. As we have seen, Germany had been on the cusp of checking out in spring 1915, only to be propped up against the ropes to be pummelled some more. Various contacts were made with the French from late 1914 onwards and peace offers were also made to the Tsar. Bethmann assured the Russians that Germany wanted “only small concessions in order to protect our eastern border, as well as final and commercial treaties” (126) and even offered free passage through the Straits, Russia's holy grail, to no avail.

In September of 1916, the Germans had asked Wilson to broker a peace in return for German withdrawal from Belgium, but he refused to get involved prior to the presidential election in November –(127) a curious decision, given his campaign promises and the prospect of a tight election.

Figure 5

Two months later, at the conclusion of the score draw at the Somme, the Germans went public, declaring that the Central Powers “have given proof of their indestructible strength” (128) and calling for peace negotiations. The Allies were unconvinced – it's my impression that peace overtures are more likely to be interpreted as a sign of weakness, rather than strength. Wilson, according to the official account, saw himself as a mediator and tried to prod the British and Germans into discussions, sending Col House over to grease the wheels in early 1915 and early 1916.(129) However, as already noted, House was actually striking a deal with Grey, one that would bring America into the war. To that end, the American economy had been prepped for a war effort for at least a year. Wilson had previously “rejected a number of opportunities to work in concert with neutral nations to promote mediated peace negotiations”.(130)

The Austro-Hungarians were also active in seeking peace, with initiatives in early 1917 to both the British and the Americans.(131) To an enemy intent on destruction, one imagines that their particular feelers were less likely to be successful, as they were clearly negotiating from a position of weakness. The Allies were also often intent on attempting to split the Central Powers by negotiating a separate peace with one of them, thus isolating the other. Even when in straitened circumstances, neither side was willing to abandon their version of 'honour'.

And Wilson had other motivations. Wall Street and the Fed had invested billions in an Allied victory; by 1917, the Morgans and Kuhn, Loeb & Co. had floated a billion and a half in loans.(132) In toto, the Allies were in hock to the tune of $3 billion in hard cash and $6 billion in American exports.(133) It's difficult to overstate the keenness with which the Wall Street banks lobbied for US entry into the conflict – a defeat for the Allies would inevitably result in defaults or, worse, non payment of interest on the capital.

And so, Wilson and the Allies passed on the opportunity to at least have a stab at stopping the killing. Germany and the Austro-Hungarians were to be crushed, instead – at whatever cost. Ironically, they weren't the only intended victims. Russia was also in the cross-hairs, despite her status as an Entente Power and America and her proxies were deeply enmeshed in Russian affairs. J P Morgan was in the thick of it, making the first loan to Russia in 1914 ($12 million).(134) A gentleman named Olof Aschberg was the principal intermediary, via his bank Nya Banken. However, he was also funnelling funds from the German government to Russian revolutionaries.(135)

Aschberg became the head of Ruskombank, the first Soviet international bank and a director of Guaranty Trust (an American banker) became chief of Ruskom's foreign department.(136) However, Morgan wasn't the only philanthropist dedicated to globalist machinations. Another director of Guaranty Trust and one from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York also funded revolutionary activity in Russia in 1917, illegally.(137) This intrigue took place after the Americans declared war on the Central Powers, with the expressed intention of playing a leading role in shaping the peace to best advantage.

But Russia's future did not include a role as a Great Power – at least, not if the bankers had any say in it. It's not difficult to understand the whys and wherefores. Russia was the largest untapped market in the world and the greatest potential threat to America's burgeoning industrial and financial supremacy. The likes of Morgan, Rockefeller and Guggenheim – all Wall Street behemoths – were already well known for their monopolistic tendencies, particularly with regard to the US railroad system. Now, they were looking to impose that template on the global stage:

“The gigantic Russian market was to be converted into a captive market and a technical colony to be exploited by a few high-powered American financiers and the corporations under their control.”(138)

How best to accomplish this end? Well, they were nothing if not resourceful, but they needed the cooperation of the Germans – not yet the enemy, officially. They had their pet revolutionaries standing by, Lenin in Switzerland and Trotsky in New York. And the Germans figured that they had plenty to gain from the arrangement, too, if they could help engineer a Russian exit from the war. They also had their eyes on 'the war after the war', if they could emerge from the present conflagration intact. And so, improbably, Germany and Wall Street had formed an alliance – and Wilson, the bankers' place-man, did his bit. That sabotaging Russia also meant more dead Frenchman and Brits on the Western Front did not trouble the likes of J. P. Morgan one whit.

Trotsky was funded by the German government, through American proxies – the same banks that, prior to 1917 and America's entry to the war, raised funds on the British money markets for the German government and which also funded German espionage in the United States.(139) The banks were not alone in their amorality:

“All through the war the great armament firms were supplied from the enemy countries. The French and the British sold war materials to the Germans through Switzerland, Holland and the Baltic neutrals, and the Germans supplied optical sights for the British Admiralty. The armament industry, which had helped stimulate the war, made millions out of it.”(140)

But they were much more proactive. Lenin returned to Russia after the establishment of what, even contemporaneously, was known as the 'Provisional Government' after the first revolution in February, passing through the German lines in order to do so, with the blessing of Warburg's brother (the German spymaster) and was secretly financed by the Guaranty Trust Company (another J P Morgan controlled entity) via a cut-out bank in Stockholm.(141) Charles Crane, a former chairman of the Democratic Party's Finance Committee, was in Russia, baby-sitting phase one.

Trotsky, in possession of a US passport - arranged by Wilson himself – and a Russian entry permit, was waved off from New York at the end of March and, promptly detained by the Canadians and the British at Nova Scotia.(142) Prominent Americans lobbied for his release – even though Trotsky had declared his intention to overthrow the Provisional Government – and he was allowed to continue on his way by the British government (likely at the instigation of Alfred Milner, a transatlantic Col House, figurehead of the British Deep State). Wall Street bankers then spent months in Russia (July-November 1917), under the guise of a Red Cross mission, all expenses paid by William Thompson of the Federal Bank of New York.(143) Thompson returned stateside prior to the November re-revolution, leaving Raymond Robins, a Bolshevik sympathiser, in charge.

It seems probable that American involvement was predominantly the product of private bankers and Wilson himself, both with somewhat divergent aims. The State Department, during the summer of 1917, wanted to prevent “injurious persons” (aka Russian revolutionaries) departing the US, but were unable to do so as many were in possession of new American passports.(144) The Root Commission, led by a former Secretary of State, was also in Russia, attempting to pressure the Provisional Government into staying in the war,(145) while the Petrograd Soviet – which shared power – was doing its best to sabotage the war effort.

The United States opened a line of credit worth $100 million in March, which had increased to $350 million by August, contingent on continued Russian aggression.(146) My impression is that the bankers were working at cross-purposes with the bulk of the US government and that Wilson may have been misled as to the true intentions of Trotsky and Lenin. He supported the Provisional Government – he was, after all, a progressive – but wanted Russia to keep fighting, which Lenin, from his rhetoric, was set against.

The bankers, having facilitated the November revolution and – presumably – knowing their men, only seemed to care about ensuring that it was them, not the Germans, who got to exploit the new market.(147) The other half of the partnership, the German government, achieved its initial objectives, too. They had assessed “Lenin's probable actions in Russia as being consistent with their own objectives”,(148) an objective that had already borne fruit as of February.

The modern consensus seems to hold that the Russian armies were destined to lose the war after 1916 – given the massive losses incurred by some of the less competent generals in the year's offensive – but this is false. Russian industry was now up to speed (149) and the troops were in excellent condition, well supplied, well fed and well trained. They enjoyed a 1.5-1 numerical advantage over the Austro-Hungarians opposing them, the latter judging that more than 72% of the Russian divisions were “outstanding units” and “first-class troops”.(150)

But the February Revolution put paid to that, killing morale and leading to a huge wave of desertions. Whilst most troops remained at the Front, there was no longer any appetite for offensive manoeuvres. Alexander Kerensky, Minister of War and poisoned chalice-holder, attempting to fulfil Russia's commitment to the Triple Entente, which called for an offensive in the spring, instead launched it in the summer, by which time front-line units had elected soldiers' committees and the chain of command was severely compromised.(151)

Kerensky believed that a successful offensive in Galicia would restore morale and the Army had over seven million soldiers in the field.(152) However, delays and political ambivalence bedevilled preparations and, although the Soviet “called on soldiers to go on the offensive against the Central Powers to prevent the disintegration of the army, put Russia in a better negotiating position to end the war, and defend the territory of the country”,(153) the Bolsheviks and other elements called it part of an “imperialistic war”.(154)

By now, of course, Wilson had persuaded Congress to declare war on Germany, which it did on 6th April, only two-and-a-half months after he had been re-elected. Ostensibly, the trigger was a resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare – announced by the Germans on 1st February – which had resulted in the loss of ten American ships,(155) but which had been precipitated by America's 'active neutrality', the practical effect of which was to arm the Allies and allow them to persist with a blockade that was in breach of international law. The British were also arming merchant ships, disguising warships as merchantmen and using neutral ships as cover.(156) My assumption is that these actions were not within the public square, as sentiment in the United States had undergone something of a sea change:

“During the period of U.S. neutrality from 1914 to 1917, American sentiment shifted gradually but inexorably toward a pro-Ally, pro-war position, first because of the sophisticated British propaganda campaign, and then from the increasing pressure from business and corporate elite on both sides of the Atlantic who had a financial and commercial stake in a British and French victory.”(157)

Pro-war fervour had also been whipped up by the delayed disclosure of the Zimmerman Telegram, a coded telegram from the German Foreign Minister to the the German ambassador in Mexico, intercepted by the British on 16th January, who were tapping American cables without their knowledge.(158) It wasn't until 23rd February that the Americans were informed, after much laundering of the gist of the message which spoke in hypotheticals; if the United States forswore neutrality upon Germany's resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare, an alliance was proposed between Germany and Mexico, who would be supported in efforts to reclaim lost territory in New Mexico, Texas and Arizona.(159)

Had it not been these provocations, another reason would have been found. Wilson finally had his war, just as the Russians were gearing up for the Kerensky Offensive and the French were three days away from their own attack in the West. The world was to be made safe for democracy. As Senator Robert LaFolette noted:

“Let us look at the company we will keep in performing this benevolent function. We will be marching side by side with the King of Serbia; the King of Italy is our boon companion; the King of Belgium is there; so also the King of Roumania; the Emperor of India and the King of England, our stalwart brother; not to mention the King of Montenegro and various other principalities and rulers, as well as chaotic Russia – only France is a Republic – and last but not least we are to be brothers in blood with our dear friend the Emperor of Japan. And this our Chief Executive proposes as our ‘league of honor.’”(160)

Wilson had been floating the promise of a more peaceful world order for some time, a new League of Nations being his preferred vehicle at war's end. Yet such an arrangement did not require that the US enter the war, merely that she mediate the peace. Further, there were options with regard to the submarine threat against American ships; he could have “refused to permit the sailing if any ship from any American port to either of these military zones” and insisted that British ships delivered the cargoes,(161) but he didn't even take the precaution of warning US passengers sailing on belligerent ships in war zones. The resultant loss of life was simply collateral damage.

But before American troops could deploy to the Western Front, the British launched an offensive at Arras on 9th April, to be joined a week later by a French attack at Aisne, both being part of the Nivelle Offensive – an attempt to break through German defences and return to a war of movement against numerically inferior opponents. The British made gains in the first two days and a Canadian Corps captured an important ridge, but momentum was slowed as the Germans stopped the gaps with reserves. Had the battle ended there, it would have been counted an Allied victory but, predictably, it didn't and by the time the offensive was called off (on 17th May), the British had suffered 150,000 casualties and gained little ground since Day One.(162)

Further south, in the main attack, the French advanced the front line around four miles, but could not land a decisive blow. Casualties were, once again, severe with some divisions suffering rates of 60% or more. The offensive was “abandoned in confusion on 9th May”,(163) six days after mutinies broke out, eventually affecting nearly half of the French divisions on the Western Front. As in the East, troops were prepared to defend themselves and remained in the trenches, but refused orders to attack.(164)

By this point in proceedings, over a million French soldiers had been killed and the failure of this attack – when the commander General Nivelle had promised a decisive victory – was too much for the Army. A new commander, Pétain, restored morale, but it wasn't until early 1918 that the task was complete. The High Command became reluctant to order another offensive for fear of the response from the infantry and France planned to “wait for the Americans and meanwhile not lose more”.(165) It was, perhaps, surprising that protests of this type had not already occurred. Although the Germans did not learn of them at the time and were unable to take advantage, their defensive prowess was again on display.

Waiting for the Americans was the last thing on the mind of Field Marshal Haig, who had had his eye on Ypres since the end of 1915. The Admiralty was keen to neuter the U-boat threat by obtaining control of the Belgian coast and the overall strategy for 1917 was to wear the Central Powers down with constant attrition on every front.(166) Nonetheless, Haig did not receive approval for a Flanders campaign until 25th July, and even then there was opposition in the form of Lloyd George and General Foch, the French Chief of Staff.(167) The wisdom of pursuing an offensive strategy in the wake of the Nivelle Offensive remains questionable.

As it was, a series of battles between 31st July and 10th November – including two that bear the name Passchendaele – made gains, depleted the Germans but failed to reach the coast and cost around 400,000 casualties, a number nearly double that of the Germans who, in their own words, “had been brought near to total destruction (sicheren Untergang) by the Flanders battle of 1917”.(168) Lloyd George, writing twenty years later, was trenchant:

"Passchendaele was indeed one of the greatest disasters of the war ... No soldier of any intelligence now defends this senseless campaign ..."(169)

The futility of the campaign is encapsulated by the before and after pictures of the village itself.

Figure 6

But results in the West were a raging success when compared with Kerensky's travails in the East. After two days of initial gains, the troops of the Seventh Army were no longer willing to continue the attack. The Eleventh Army's resolve proved a little stronger, but by the sixth day, they too stayed put. By then, 6th July, they had gained about three miles.(170) The Russian Eighth Army fared better, advancing 15-20 miles against poorly deployed Austro-Hungarians, but was forced to withdraw by the 23rd as a German counterattack on the other armies led to a full retreat that turned into a rout, despite their numerical superiority:(171)

“By the time the German counteroffensive was finished the Russian army had fallen back to the original Austria-Russian border, having retreated by as much as 120 kilometres (75 miles)”.(172)(173)

The only shaft of light in the East was provided by the Romanians, with three Russian armies in a supporting role. They managed to retake some territory and, in so doing, restored their credibility, but it was clear that the revolutionary spirit amongst the Russian troops was not about to dissipate. Now that they were back on home turf, they became more willing to fight, but offensive operations were still going to be problematic. Intrigues on the home front came to the fore, the Bolsheviks increased their influence and, on 24th October, Lenin emerged from hiding. On 7th November, the final phase of the coup d'etat was completed and Lenin announced that he would be seeking an immediate end to the war.

An armistice between the Russian Republic and the Central Powers was signed on 15th December 1917 and, with this agreement, Russia de facto exited the war, abandoning her allies in the process, who maintained “an angry stony silence”.(174) The Bolsheviks immediately launched offensives against Ukraine and other separatist governments in the Don region, while their representatives repaired to Brest-Litovsk. Negotiating from a position of abject weakness is never advisable and, when discussions broke down in February, the Russian Civil War was in full swing.

The Central Powers launched one last offensive, the Eleven Days War, and captured huge territories in Estonia, Latvia, Belarus and Ukraine, forcing the Bolsheviks to capitulate, ceding a quarter of Russia's population and industry and nine-tenths of the coal mines.(175) But Wall Street was still well-positioned, its representative (Robins) was still in frequent contact with Lenin and all else was chaff:

“Whether the Russian people wanted the Bolsheviks was of no concern. Whether the Bolshevik regime would act against the United States — as it consistently did later — was of no concern. The single overwhelming objective was to gain political and economic influence with the new regime, whatever its ideology.”(176)

Figure 7

The treaty freed up a million soldiers for the Western Front and allowed Germany to use “much of Russia's food supply, industrial base, fuel supplies and communications with Western Europe”.(177) The Allies believed that similar, severe terms would be imposed on them also if they lost in the West. Few American troops had arrived in Europe prior to January 1918, although the first 'Doughboys' had landed in June 1917. The first major operation that American infantry was involved in didn't come until 4th July.

The British had attacked at Cambrai on 20th November 1917, with the first mass tank attack. Over 300 tanks and twelve divisions overwhelmed the two German divisions defending the Front and the attackers penetrated further in six hours than they had in four months at Ypres, at the cost of 'only' 4,000 casualties.(178) The Germans came to the conclusion that there were no 'quiet fronts' any more and that they were newly vulnerable when the going was firm, but the first mass use of Stormtroopers had also shown the British to be susceptible to infiltration tactics.

However, the German High Command determined that the only way to victory was to launch a decisive attack in the spring, before American manpower became overwhelming. The thirty three divisions released from the East gave them a marginal advantage in manpower. The Entente was depleted and unable to attack and the majority of Americans were still training. The main attack was to be against the British sector, in an attempt to split the Front, outflank the enemy and defeat them. It was expected that the French would then come to terms and the Americans would be rendered irrelevant.

The main attack – Operation Michael – was to be in the Somme area, once again and, on 21st March, the biggest barrage of the entire war was unleashed – 1,100,000 shells were fired in five hours.(179) The Brits hadn't played defence since 1915 and were immediately undone as;